Mohs surgeons are dermatologists who have performed additional fellowship training to become experts in Mohs micrographic surgery. As a fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon, Dr. Gogia is highly skilled in all aspects of the technique, including surgical removal of the tumor, pathologic examination of the tissue, and advanced reconstruction techniques of the skin.

MOHS SURGERY

Please wait while you are redirected...or Click Here if you do not want to wait.

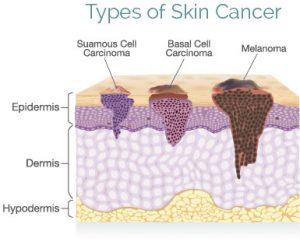

The vast majority of skin cancers in the United States are either basal cell carcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma are distinct from melanoma, a less common type of skin cancer. Fortunately, non-melanoma skin cancers such as BCCs and SCCs rarely spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body. SCCs do have a slightly higher risk for spread than BCCs, although this risk is still very low. The risk for metastasis is increased for larger, untreated tumors and in patients who are immunosuppressed. There are several subtypes of BCCs and SCCs; these subtypes can sometimes be determined by the growth pattern seen upon microscopic examination of the tissue obtained by skin biopsy. For example, some tumors have “roots,” while others grow in small clusters of cells. What you see on your skin may be only a small portion of the whole tumor. Mohs surgery is the most effective way to evaluate the tissue to ensure that the skin cancer is completely removed, while taking only as much skin as is necessary. Mohs micrographic surgery (MMS) is a highly specialized, state-of-the-art technique used for the treatment of skin cancers. Named after Dr. Frederic Mohs, the surgeon who initially developed the procedure, Mohs surgery is different from routine surgical excision. With the Mohs technique, surgically removed tissue is carefully mapped, color-coded, and thoroughly examined microscopically by the surgeon on the same day of surgery. During this process, 100% of tissue margins are evaluated to ensure that the tumor is completely removed prior to repairing the skin defect. Mohs micrographic surgery results in the highest cure rate (97-99%) for skin cancers while minimizing the removal of normal tissue. With standard surgical excision, only approximately 1% of tissue margins are examined and the results are only available days after the surgery. If cancer cells are found to remain during that delayed pathologic examination a second surgical procedure will be required at a later date. Mohs surgeons are dermatologists who have performed additional fellowship training to become experts in Mohs micrographic surgery. As a fellowship-trained Mohs surgeon, Dr. Gogia is highly skilled in all aspects of the technique, including surgical removal of the tumor, pathologic examination of the tissue, and advanced reconstruction techniques of the skin. The tumor site is locally infused with anesthesia to completely numb the tissue. You will be awake for the procedure; general anesthesia is not used. Once the skin has been completely numbed, the tumor is gently scraped with a curette to get a better sense of the clinical extent of the tumor. The first thin, saucer-shaped “layer” (or “stage”) of tissue is then surgically removed by the Mohs surgeon. An “electric needle” may be used to stop the bleeding. This process takes approximately 10-20 minutes. Once a “layer ” of tissue has been removed, a “map” or drawing of the tissue and its orientation to local landmarks is made to serve as a guide to the precise location of the tumor. The tissue is labeled and color-coded to correlate with its position on the map. The tissue sections are processed and then examined by the surgeon to thoroughly evaluate for evidence of remaining cancer cells. It takes approximately 60 minutes to process, stain and examine a tissue section. During this processing period, your wound will be bandaged and you may leave the procedure room. If any section of the tissue demonstrates cancer cells at the margin, the surgeon returns to that specific area of the tumor, as indicated by the map, and removes another thin layer of tissue only from the precise area where cancer cells were detected. The newly excised tissue is again mapped, color-coded, processed and examined for additional cancer cells. If microscopic analysis still shows evidence of disease, the process continues layer-by-layer until the cancer is completely removed. By beginning early in the morning, Mohs surgery is generally finished in one day. Very rarely, a tumor may be extensive enough to necessitate continuing surgery a second day. This selective removal of tumor allows for preservation of as much of the surrounding normal tissue as is possible. Because this systematic microscopic search reveals the roots of the skin cancer, Mohs surgery offers the highest chance for complete removal of the cancer while sparing normal tissue. Cure rates typically exceed 99% for new cancers and 95% for recurrent cancers. Fellowship-trained Mohs surgeons are experts in the reconstruction of skin defects whose goal is to preserve normal function and maximize the cosmetic outcome with each reconstructions. The best method for repairing the wound following surgery can only be determined after the cancer is completely removed, as the size and shape of the final defect cannot be predicted prior to surgery. Stitches may be used to close the wound side-to-side, or a skin graft or a flap may be utilized. Occasionally, a wound may be allowed to heal naturally. Although every effort will be made to offer the best possible cosmetic result, you will have a scar. It is not possible to surgically remove a skin cancer without a scar. The scar can be minimized by the proper care of your wound and will continue to improve and become less noticeable for up to 12 months after surgery. Healing by spontaneous granulation (also called “second intent”) involves letting the wound heal by itself. There are certain areas of the body where the body will heal a wound as nicely as any further surgical procedures. The healing time depends on the size, depth and location of the wound. Often, the surgical defect can be repaired by stitching it into a straight line (“linear closure”). This involves some adjustment of the wound and sewing the skin edges together. If possible, an attempt is made to hide the scar (within natural lines of your skin, for example). The scar is often longer than patients expect to ensure that the skin lays down flat (rather than “puckering”). In situations where a linear closure is not possible, a skin flap may be utilized. Skin flaps involve movement of adjacent, healthy tissue to cover a surgical site. Where practical, they are chosen because of the excellent cosmetic match of nearby skin. Skin grafts involve covering a surgical site with skin from another area of the body. There are three types of skin grafts. The first is called a split-thickness graft. This is a thin shave of skin, usually taken from the thigh or behind the ear, which is used to cover a surgical wound. The second graft-type is the full-thickness graft. This graft provides a thicker layer of skin to achieve desired results. In this instance, skin is usually removed from behind the ear or around the collarbone (the donor site), and stitched to cover a wound. The donor site is then sutured together to provide a good cosmetic result. A third type of graft uses skin and cartilage. This usually comes from the ear and may be used to repair defects of the nose. In rare cases, when Mohs surgery is extremely extensive or when removal of the tumor results in functional impairment, we may recommend that you visit one of several consultant surgeons for reconstruction. Mohs surgery is completed on an outpatient basis. The best preparation for surgery is a good night’s rest followed by breakfast. Please shower and shampoo your hair within 24 hours before your procedure. This will minimize the bacterial growth on your skin and help prevent infection. Mohs surgery involves a lot of waiting. Since you can expect to be here for most of the day, it is wise to bring a book or magazine to read. You can also bring snacks or lunch. Also, because the day may prove to be quite tiring, it is advisable to have someone accompany you on the day of surgery to provide companionship and to drive you home. Your appointment has purposely been scheduled early in the day. When all of your questions have been addressed and your records reviewed, the surgery will begin. The removal of each layer of tissue takes approximately one to two hours. Only 10-20 minutes of that time is spent in the actual surgical procedure, with the remaining time being required for slide preparation and interpretation. As Mohs surgery is often used to treat complex skin cancers, up to 2/3rds of all treated tumors required 2 or more stages for complete removal. Once we are sure that we have totally removed your skin cancer, we will discuss with you our recommendations for repairing your surgical wound. Swelling and bruising are very common following Mohs surgery, particularly when it is performed around the eyes. It can appear fairly dramatic and may result in the appearance of a “black eye.” The swelling and bruising may peak at 48-72 hours after surgery and usually subsides within four to five days. We recommend the use of an ice pack in the first 48 hours. Most people are understandably concerned about pain after the procedure. Fortunately, the vast majority of patients will have little or no pain; those that do experience pain usually gain relief by taking Tylenol (acetaminophen). In some cases, you may be prescribed a stronger pain medication. We ask that you avoid taking aspirin or ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) as they can increase the risk of bleeding. A small number of patients will experience some bleeding post-operatively. This bleeding can usually be controlled by applying direct, firm pressure over the bleeding site for at least 15 minutes; DO NOT lift relieve pressure during that period. If bleeding persists after continued pressure for 15 minutes, repeat the pressure for another 15 minutes. If this fails, please call the on-call physician. There are some minor complications that may occur after Mohs surgery. A small red area surrounding your wound is normal and does not necessarily indicate infection. Please notify us if you develop a fever, chills, swelling or drainage, or escalating pain. Itching and redness around the wound, especially in areas where adhesive tape has been applied, are not uncommon. When this occurs, ask your pharmacist for a non-allergenic tape. Often, the area surrounding your operative site will be numb to the touch. This area of anesthesia (numbness) may persist for several months or longer before improving.We specialize in Mohs Micrographic Surgery

A Guide to Mohs Micrographic Surgery

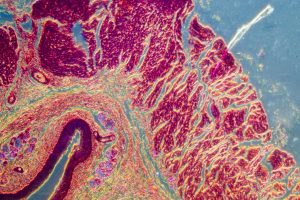

Skin cancers are the result of uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells at an unpredictable rate. As cancers grow, they destroy the surrounding normal, healthy tissue. The most common cause of skin cancer is long-term exposure to ultraviolet light; as you might expect, skin cancers most often occur on sun-exposed areas of the body such as the head and neck.

Skin cancers are the result of uncontrolled growth of abnormal cells at an unpredictable rate. As cancers grow, they destroy the surrounding normal, healthy tissue. The most common cause of skin cancer is long-term exposure to ultraviolet light; as you might expect, skin cancers most often occur on sun-exposed areas of the body such as the head and neck. Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) grow from specific cells in the skin. These tumors are often referred to as non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs). Skin cancers often begin as a small bump that can be mistaken for a pimple or a blemish. Over time, the lesion grows and may bleed or become sore. Some skin cancers appear red, somewhat translucent, or scaly.

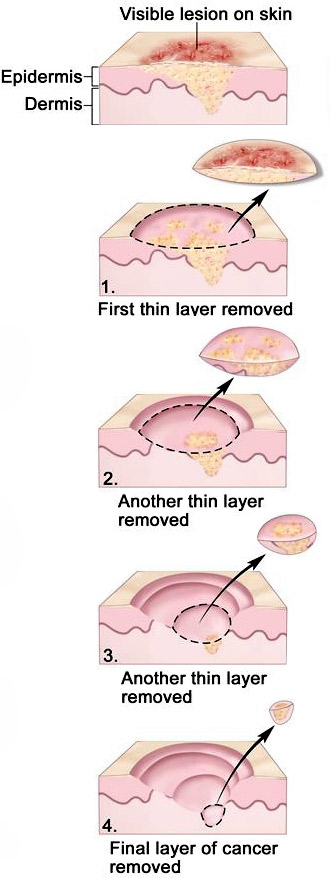

Basal cell carcinomas (BCCs) and squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) grow from specific cells in the skin. These tumors are often referred to as non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs). Skin cancers often begin as a small bump that can be mistaken for a pimple or a blemish. Over time, the lesion grows and may bleed or become sore. Some skin cancers appear red, somewhat translucent, or scaly. The Mohs surgical process involves a repeated series of surgical excisions followed by microscopic examination of the tissue to assess if any tumor cells remain. Some tumors that appear small on clinical exam may have extensive invasion underneath normal appearing skin, resulting in a larger surgical defect than would be expected. It is not possible to predict a final size until all surgery is complete. Approximately 2/3rds of all tumors treated with the Mohs surgery require 2 or more stages for complete excision.

The Mohs surgical process involves a repeated series of surgical excisions followed by microscopic examination of the tissue to assess if any tumor cells remain. Some tumors that appear small on clinical exam may have extensive invasion underneath normal appearing skin, resulting in a larger surgical defect than would be expected. It is not possible to predict a final size until all surgery is complete. Approximately 2/3rds of all tumors treated with the Mohs surgery require 2 or more stages for complete excision.Step 1: Anesthesia

Step 2: Removal of visible tumor (1st stage)

Step 3: Additional stages (if necessary)

Step 4: Reconstruction

Swelling/Bruising

Pain

Bleeding

Complications

Expectations

Want to schedule an appointment?